Amateur history nerd that I am, I’m quite pleased to have married into a family which has retained all sorts of books, newspapers and magazines dating from about 1920 onwards. The “In the Hausarchiv” series gives an occasional look at the things I’ve come across in our own “house archive”.

Amateur history nerd that I am, I’m quite pleased to have married into a family which has retained all sorts of books, newspapers and magazines dating from about 1920 onwards. The “In the Hausarchiv” series gives an occasional look at the things I’ve come across in our own “house archive”.

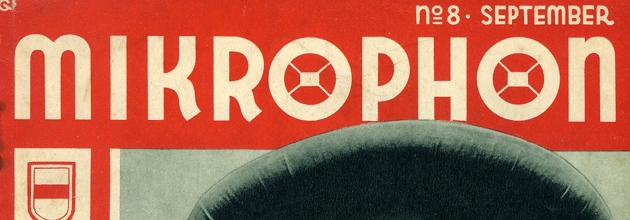

Today’s “In the Hausarchiv” features the September 1934 edition of the small-format magazine, Mikrophon, a “magazine for radio listeners” produced by what was, at the time, the official Austrian radio broadcaster (RAVAG).

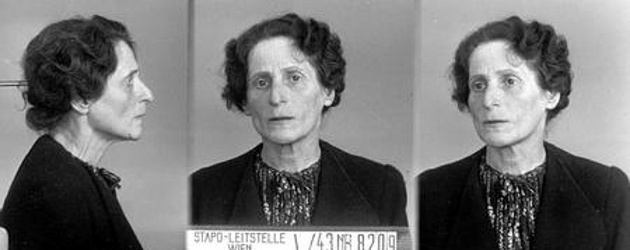

The cover of this September 1934 edition shows a young man wearing traditional garb (Carinthian, perhaps?), a photo which hints at one of the features within the edition, namely a story about traditional Austrian costume (“Österreichische Volkstrachten“). But of real interest to me is the first story inside: “Österreichs Heldenkanzler ist tot … !” (“Austria’s heroic chancellor is dead … !”; see scanned image). This refers to the July 1934 murder of Austria’s chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss.

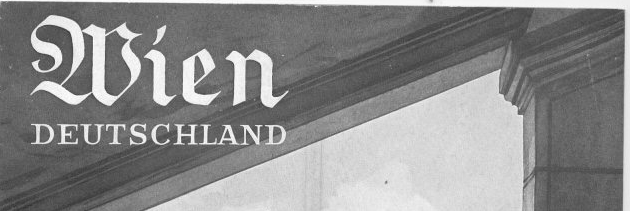

I know that, to many people, Austrian history is rather obscure. People with “passing” knowledge of the years surrounding World War Two might know of the Anschluss of 1938, when Nazi Germany occupied and then dissolved Austria, merging it into Germany. But I think relatively few people these days know that the Nazis attempted a Putsch in Austria already in 1934. It was via this Putsch that the life of the Austrian Chancellor at the time, Engelbert Dollfuss, ended; one of the Nazis who stormed the Chancellery shot him twice.

I know that, to many people, Austrian history is rather obscure. People with “passing” knowledge of the years surrounding World War Two might know of the Anschluss of 1938, when Nazi Germany occupied and then dissolved Austria, merging it into Germany. But I think relatively few people these days know that the Nazis attempted a Putsch in Austria already in 1934. It was via this Putsch that the life of the Austrian Chancellor at the time, Engelbert Dollfuss, ended; one of the Nazis who stormed the Chancellery shot him twice.

Dollfuss himself was basically a dictator, more like the Mussolini of 1934 than the Hitler of 1934, but even more so like one might expect a Catholic dictator following some of the social tenets of Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum to be. Generally speaking, there was no broad terror associated with his dictatorship. His major concern at the time of his death in 1934 seems to have been to save Austria from Germany. With that goal in mind, he tried various ways to instill a specifically Austrian patriotism to counter the German nationalism which attached many of his subjects to the big northern neighbor and its Führer. If I sound like I’m minimizing the dictatorial aspects of Dollfuss’s regime, well it’s simply because I’m not very “impressed” with his stature amongst the 20th Century European dictators. I’m being a bit tongue-and-cheek here: by saying I’m not “impressed” I mean that Dollfuss and his followers didn’t murder and invade like the others. This isn’t to say his regime wasn’t repressive. In fact, here in the 21st Century, a good Austrian Social Democrat would probably jump down my throat for any hints of minimization of the Dollfuss dictatorship such as I’ve presented so far in this paragraph. Dollfuss did, after all, ban the Social Democrats (and the Nazis, for that matter.) He ended the parliamentary republic of Austria and instituted one party rule (the “Fatherland Front”). He was a dictator, plain and simple. He just happened to be nowhere near the meanest of the group of dictators that plagued Europe around that time. (Of course, that doesn’t mean he would not have become as bad as the others…)

Anyway…

The small set of paragraphs beneath Österreichs Heldenkanzler ist tot!, as shown in the image, provide us with a nice example of precisely the kind of patriotism which Dollfuss attempted to instill in the Austrian people. An excerpt:

“Österreich über alles, wenn es nur will.” — Dollfuss hat das Wort geprägt, und sein von glühender Vaterlandsliebe beseelter Optimismus hat es hinausgetragen bis in die fernsten Täler seiner unvergleichlich schönen Heimat, hat es tief hineingegraben in das Herz seines Volkes.”

I find it somewhat difficult to translate that first part: Österreich über alles, wenn es nur will. Many of you may have heard or read the words “Deutschland (, Deutschland) über alles” (which, contrary to the belief of many, did not come from the Nazis). One English analog to “über alles” might be “first”, in the sense meant by the America First Committee of the early 1940s. In other words, “Austria (or Germany) is important above all other considerations”. Then the “wenn es nur will” part means, “if it would just want it”, i.e., if it was simply willing to believe in itself and fight for itself. It’s a strong call to patriotism, which we might translate, in a much more wordy fashion, like this:

Austria First! It can prevail, if only it would believe in itself!

Then, with the rest (“Dollfuss hat das Wort…”):

“Austria First! It can prevail, if only it would believe!” — Dollfuss coined this saying, and his optimism, animated by a burning love for his Fatherland, carried it to the nethermost valleys of his incomparably beautiful homeland and buried it deep into the heart of his people.

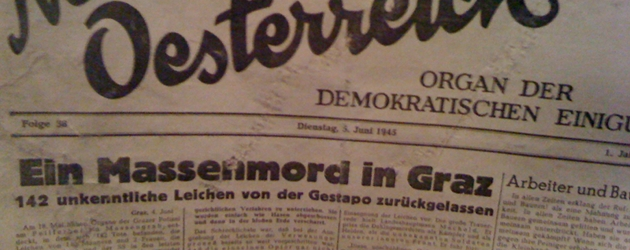

One can imagine that RAVAG, the radio broadcaster which published this magazine to its listeners, had a special hatred for whom they describe as “feige Mörder” (cowardly murderers). For on the day of the Putsch, 25 July 1934, the Putschists raided and occupied two buildings: the Chancellery where Dollfuss was killed, and … RAVAG! The following excerpt comes from Gordon Brook-Shepherd’s excellent Dollfuss (Amazon US, UK):

The storming of the Government headquarters had been the rebels’ first success. Their second was the seizure soon afterwards of the main Austrian RAVAG studios in the Johannesgasse from where, at lunch-time, they managed to broadcast a brief message announcing the “resignation” of Dollfuss and the appointment of Dr. Rintelen as his successor.

The Putsch fizzled out on that day and the Austria of the “Fatherland Front” survived to live another four years before being gobbled up by the rather more mean dictatorship from the north.

P.S. One of my favorite books concerning Austrian History covers the idea of Austrian neutrality and how it came about. The book is Gordon Brook-Shepherd’s The Austrians: A Thousand-Year Odyssey. (That link is for Amazon.com, but it’s also available from Amazon.ca, Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.de.)

P.S. One of my favorite books concerning Austrian History covers the idea of Austrian neutrality and how it came about. The book is Gordon Brook-Shepherd’s The Austrians: A Thousand-Year Odyssey. (That link is for Amazon.com, but it’s also available from Amazon.ca, Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.de.)