I’ve chosen a German book for this week’s Book of the Week. Unfortunately, Wolfgang Welsch’s Ich War Staatsfeind Nr. 1 (I Was State’s Enemy Number 1) is not available in English. That’s really too bad because the story is pretty amazing.

Welsch was born in Berlin in 1944. His family ended up in the eastern sector after the war, and therefore later became citizens of the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany). As early as the 1960s, Welsch began to protest the regime through his poems, public readings and pamphlets. He attempted to escape the country but was apprehended. While awaiting trial, he was mistreated and tortured by agents of the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (Stasi). After conviction, he spent several years in the Bautzen and Brandenburg prisons.

The Federal Republic of Germany (FRG/BDR, Bundesrepublik Deutschland, West Germany) purchased Welsch’s freedom in 1971. During the 70s and 80s, he became one of the most successful Fluchthelfer — people who assisted East Germans who wished to escape the regime.

I’ll finish the story here simply by pasting in a (not particularly good) translation I did of the synopsis of Welsch’s book several years ago. This will make this post the longest, by far, here at German History Blog — so if you don’t want the nitty gritty details, let me give you the executive summary here: Welsch’s success helping people emigrate from East to West made him a target of the Stasi (though, you’ll recall, Welsch was by now a citizen of West Germany). He became a marked man and Stasi agents operating in the West made at least three attempts on his life: once by putting a bomb in his car (it detonated but injured him only slightly); once by shooting into his vehicle as he drove on a highway in the UK, and once via introducing Thallium in his food. Only after the Wall fell did it become possible to scour the Stasi files and find direct evidence of these assassination attempts. This led eventually to the trial of a former Stasi Major-General, who committed suicide in prison.

Wolfgang Welsch’s story was adapted into a German television film which first appeared on 13 April 2005 and has been shown several times since (including just a few days ago.)

If you can read German and this period of German history interests you — particularly if you are or had been under the impression that East German security services did not take part in assassinations –, then I highly recommend to you Wolfgang Welsch’s Ich war Staatsfeind Nr. 1.

Photo Credit

The lead photo for this article comes via Wikimedia from the German Federal Archives. It shows the prison at Bautzen, in which Wolfgang Welsch was interred as a political prisoner.

—

Begin excerpt of the synopsis of Ich war Staatsfeind Nr. 1 (my translation) —

…

Part II

After the dramatic crossing of the border in a GDR government bus, Welsch settles down in Giessen and begins to study sociology, philosophy and politics, while simultaneously preparing for his debut as an active underground facilitator for East Germans who wanted to flee. Together with a friend from his days in prison, he fetches a professor out of the GDR. The operation is planned in the Federal Republic of Germany and carried out from Athens, Greece. Welsch flies to Sofia as a courier, delivers a prepared West German passport to the refugee, gives the necessary instructions, and flies back to Athens via Bucharest, Romania. The escape is a successful “David versus Goliath” story: Wolfgang Welsch against one of the best Secret Services in the world.

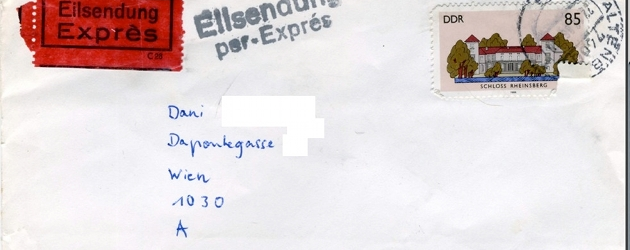

Welsch is in charge of and takes part in the most daring escape missions throughout the whole of the Eastern Block. Sealed trucks, private cars, caravans, horse transporters and scheduled flights are all part of his arsenal. The route goes from East Berlin via Sofia, Bucharest and Belgrade to Vienna or Frankfurt/Main. Airline flights and diplomatic vehicles are the safest and most effective methods of extracting people from the East. Throughout this part of the book, Welsch relates these stories of liberation in detail. Highlights include a chance meeting with a CIA agent in Athens; the agent seems to know of Welsch’s activities and praises him, noting that “they” could not have done it better themselves.

In reply to a hateful article about him in an East Berlin newspaper (“Keine Chance den Menschenschmugglern” – “Don’t give the smugglers of people a chance” — horizont, 2/80), Welsch sends a telex to the MfS, mentioning not only his chances but also his successes. The Minister of State Security — the notorious Erich Mielke — is furious at this provocation and his agency forms a special task force specifically to eliminate Welsch.

Welsch’s wife at that time is arrested while attempting to aid an escape in Sofia, Bulgaria. She betrays him, the structure and planning of his organization and all the names known to her. Welsch has no suspicion of this betrayal and frees his wife from the claws of the Bulgarian Secret Service in a spectacular mission. The US Embassy in Sofia participates in this, as well as the Federal Foreign Secretary, Mr. Hans Dietrich Genscher.

During this period, Welsch battles the dictatorship not only by continuously and successfully aiding escapes, but also by publishing condemnatory articles in West German newspapers. With the help of a German political party, he sends a memorandum to the United Nations in New York to urge them against letting the GDR join the community of nations. Of course, the GDR representative at the UN receives a copy of this memorandum. The MfS Secret Police then re-double their efforts to assassinate Welsch.

Part III

For years there is a special “process” in the MfS, in which the various “tactical measures” against Welsch’s “criminal human-smuggling gang” are discussed and potential “solutions” to the problem — meaning, methods of assassination — are suggested. Around 1978, the leader of the “Central Operative Process Scorpion,” MfS Major-General Heinz Fiedler, gives the order to liquidate Welsch. MfS minister Mielke and the Central Committee of the Communist Party (SED) are informed. The murder machinery of the MfS begins to roll into action. An agent is sent to the West. His orders are to assassinate Welsch. This agent, whose cover name is “Alfons”, pretends to be a friend and succeeds in winning Welch’s confidence. “Alfons” constructs a car bomb using the explosive Semtex 1A, which he receives from the GDR Secret Service. He installs the bomb under the dashboard in Welsch’s car. While Welsch drives on the motorway, the delay-action explosive detonates, completely destroying the car. Miraculously, Welsch survives with only minor injuries.

After this failure, “Alfons” lures Welsch to London. As Welsch drives along an English motorway, a sniper is lying in wait. This time the team of General Markus Wolf, leader of the MfS’s Foreign Agent Department, is also involved in supporting the operation. In England, a NATO member state, an East German agent alongside the motorway shoots at Welsch, but misses his target by a hair’s breadth. Welsch has no idea what really happened; he thinks that some fool shot at him by chance.

After these two assassination attempts fail to achieve their objective, it is finally time for agent “Alfons” to finish the job. In 1981, he lures Welsch, his then-wife and his daughter to Israel. The MfS has placed a second agent — a female — there as well. “Alfons”, who throughout all of this has meanwhile become Welsch’s closest friend, recommends a motor home for traveling around Israel. This motor home had been specially exported from Germany to Israel for this purpose. The agents’ plan is to poison Welsch using the highly toxic heavy metal Thallium. They consider Welsch’s wife and child to be acceptable collateral victims if need be. During a break at the Red Sea, Agent “Alfons” prepares a meal in the motor home’s kitchen. He deposits ten times the deadly dose of the scentless and tasteless poison into the food. Though his wife and daughter eat very little of the meal, Welsch alone consumes almost all of the poison. After a four-day incubation period, the first symptoms become visible. Both agents find excuses to leave the Welsch family and return by detours to East Berlin. Mrs. Welsch and the child feel sick for only a short time, but Welsch himself falls into agony. He feels paralyzed, almost unable to move his legs. Finally, the family manages to fly back to Germany, where doctors at the hospital fight for his life. Seriously ill, he remains in the hospital for quite some time. He eventually recovers: another miracle.

As medical experts tell Welsch that such lethal doses of poison cannot be eaten by chance, he immediately suspects the Secret Police of the GDR. After the fall of the Wall, he begins to search his files in the “Gauck department”, the agency setup to be the custodian of MfS files. He then begins searching for the assassins, an effort which takes him to England, Greece and as far as Argentina, but to no avail. One day he reads a book on the work of Eastern secret services. The book’s description of the methods employed by these Services confirms his suspicion that the attempts to murder him must have been organized by the MfS. Despite meticulously collected evidence and leads, nobody wants to believe him. Both journalists and legal authorities think that his assumption is crazy. Forty years of communist propaganda show their influence on the judgment of the West German intelligentsia. Everyone rejects his assertion that the GDR was in the business of political assassination. He files three criminal complaints, but nothing happens. Only one important news magazine in Hamburg believes him. Three journalists take interest in the case and begin their investigations. Eventually they are joined by a special investigative task force of the Berlin State Attorney’s office, constituted specifically to investigate the crimes of the former GDR. Evidence supporting Welsch’s suspicions begins to accumulate. In the meantime, Welsch himself has left Germany to live in Costa Rica after receiving further death threats.

The perpetrators of the assaults, and the MfS officials who approved them, are found and arrested. Major-General Fiedler, the head of “Operation Scorpion”, hangs himself in a Berlin prison cell. At a sensational trial, the assassin “Alfons” and his co-conspirators plead guilty. “Alfons” is sentenced to several years of prison. Another of the perpetrators dies of cancer.

— End excerpt of the synopsis of Ich war Staatsfeind Nr. 1 (my translation) —

)

)